Defying strenuous US objections and the threat of sanctions, Turkey began receiving the first shipment of a sophisticated Russian surface-to-air missile system Friday, a step certain to test the country’s uneasy place in the NATO alliance.

The system, called the S-400, includes advanced radar to detect aircraft and other targets, and the United States has been unyielding in its opposition to Turkey’s acquisition of the equipment, which is deeply troubling to Washington on several levels.

It puts Russian technology inside the territory of a key NATO ally — one from which strikes into Syria have been staged. The Russian engineers who will be required to set up the system, US officials fear, will have an opportunity to learn much about the US-made fighter jets that are also part of Turkey’s arsenal.

That is one reason the Trump administration has already moved to block the delivery of the F-35 stealth fighter jet, one of the United States’ most advanced aircraft, to Turkey, and has suspended the training of its pilots, who were learning how to fly it. (Whether NATO, in turn, might glean some Russian secrets from Turkey’s acquisition of the S-400 is unclear.)

But the problem runs far deeper. A breach with Turkey over the S-400 casts into question the future of the Incirlik air base, a critical post for US forces in the region. And while US officials never discuss it in public, the base is also the storage site for scores of US tactical nuclear weapons, a leftover of the Cold War.

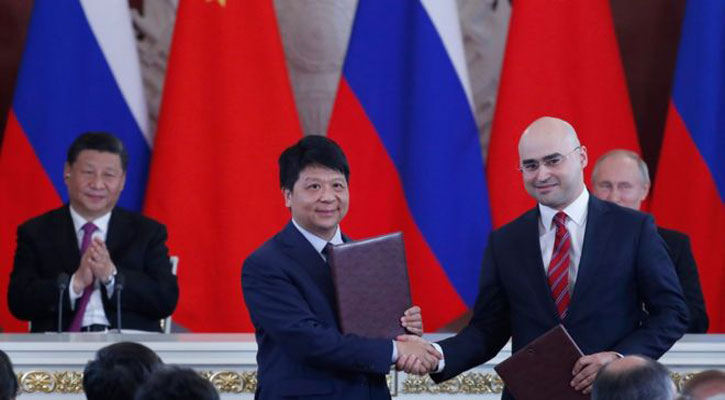

To the minds of Pentagon strategists, the S-400 deal is part of President Vladimir Putin’s plan to divide NATO. US officials are clearly uneasy when asked about the future of the alliance, or even how Turkey could remain an active member of NATO while using Russian-made air defences.

“The political ramifications of this are very serious because the delivery will confirm to many the idea that Turkey is drifting off into a non-Western alternative,” said Ian Lesser, director of the German Marshall Fund in Brussels. “This will create a lot of anxiety and bad feelings inside NATO — it will clearly further poison sentiment for Turkey inside the alliance.”

Strategically positioned at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, and sharing a border on the Black Sea with Russia, Turkey has long been both a vital peg in NATO and one of its more prickly members.

With one foot in the conflicts of the Middle East and a toehold in Europe, its interests have not always easily aligned with an alliance originally forged as a Western European defence against the Soviets. Instead, under the leadership of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey has increasingly played both sides in the East-West struggle.

NATO has stationed the American-made Patriot surface-to-air missile system on Turkish soil since the outbreak of the civil war in Syria, but Erdogan has insisted his country needs its own long-range system.

Turkey tried for years to buy its own Patriot system, but talks with Washington never produced a deal — a result that President Donald Trump, at the Group of 20 meeting last month, said was the fault of the Obama administration.

“It’s a mess,” Trump said. “And honestly, it’s not really Erdogan’s fault.”

Even as he announced the arrival of three planes bearing the first parts of the Russian system, Defence Minister Hulusi Akar said Turkey still hoped to buy its US counterpart. “We are looking for Patriot procurement and our institutions are working intensively in that regard,” he said in remarks shown on the state-owned TRT channel.

Turkey does need to fill a gap in its defences, but in purchasing the S-400, “the political-military outcomes could turn into a weakness for Turkey’s security,” said Ahmet Han, professor of international relations at Altinbas University in Istanbul. “The delivery has already caused a creeping vulnerability because it has damaged Turkey’s relations with NATO.”

The presence of the Russian system — which includes truck-mounted radars, command posts and missiles and launchers — would introduce an extra consideration into every NATO operation, he said, and that added strain “is the exact thing that Russia is after.”

Turkey’s turn to Russia for its own system is a success for Putin, who has sought to draw Turkey closer since a dramatic falling-out over the Syrian war, in which the Kremlin has backed the Assad government, while Turkey has supported a rebel faction.

The S-400 delivery comes just before celebrations Monday in Turkey to mark the third anniversary of a failed coup attempt against Erdogan. That upheaval marked a turn in relations with Russia, said Diba Nigar, the Turkey director for the International Crisis Group, a research institute based in Brussels.

Many Turks, she said, believe “that NATO allies didn’t stand up for Turkey, that the West turned a blind eye during the coup but that Moscow was more supportive.”

The sale also promises to add to Russia’s growing reach in the greater Middle East. Moscow’s decisive intervention in the conflict in Syria has cemented Russia’s dominance there, and Libyan strongman Khalifa Hifter is another beneficiary of its support.

A NATO spokesman said Friday, “We are concerned about the potential consequences of Turkey’s decision to acquire the S-400 system,” in part because it is considered technically incompatible with the weapons systems used by NATO countries.

“Interoperability of our armed forces is fundamental to NATO for the conduct of our operations and missions,” said the spokesman who, in keeping with the organisation’s protocol, declined to be quoted by name. “We welcome that Turkey is working with several Allies on developing long-range air and missile defence systems.”

The Turkish and Russian defence ministries both reported that the first parts of the system arrived at the Murted airfield in Ankara on Friday. Turkish news media reported that a team of Russian specialists had also arrived to assemble the system.

Russian officials used the occasion to boast of the S-400’s effectiveness and to tweak the United States.

Turkey “came under unprecedented pressure and nevertheless prioritized national security,” Franz Klintsevich, a Russian senator, told the Interfax news agency. He claimed that Patriot missiles are made to be incapable of locking onto “a target carrying the US flag,” adding, “everyone knows that.”

“Russian S-400 systems guarantee preservation of their sovereignty,” he said of Turkey. “No wonder the Americans are irate.”